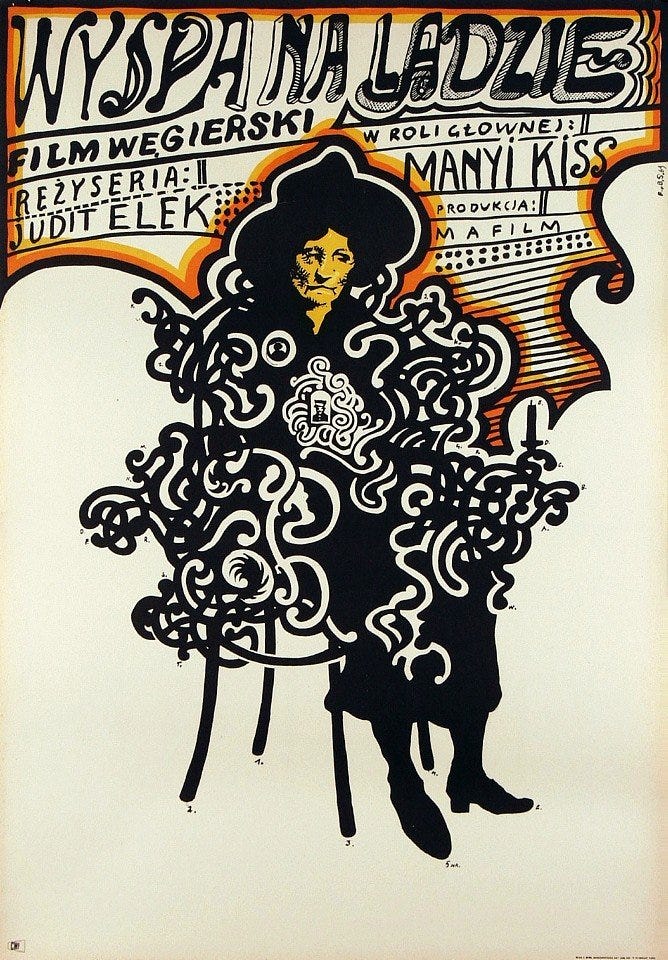

(Franciszek Starowieyski’s Polish poster for The Lady from Constantinople)

I was convinced I got it wrong. The stream had messed up. Turned out, that black screen at the start of Every Week Seven Days (1964) was just a funny way to start a movie and keep you off-kilter. I breathed a sigh of relief, lamenting with my next breath how it would feel to be in that darkness with this film. Maybe someday.

The International Film Festival Rotterdam is an event I’ve wanted to attend for years, especially after its Hubert Bals Fund appeared to support after every revelatory film I saw: Uncle Boonmee (2010), La Flor (2018) and The Little Girl Who Sold the Sun (1999) to name a few. This year, I was lucky enough to attend, but only from my sofa. The case was the same for everyone else covering the fest, as concerns over Omicron prompted the organisers to scale down and go online. While it has been convenient for me, I can’t help but think how much I’d like to be part of the IFFR experience one day when things are more settled.

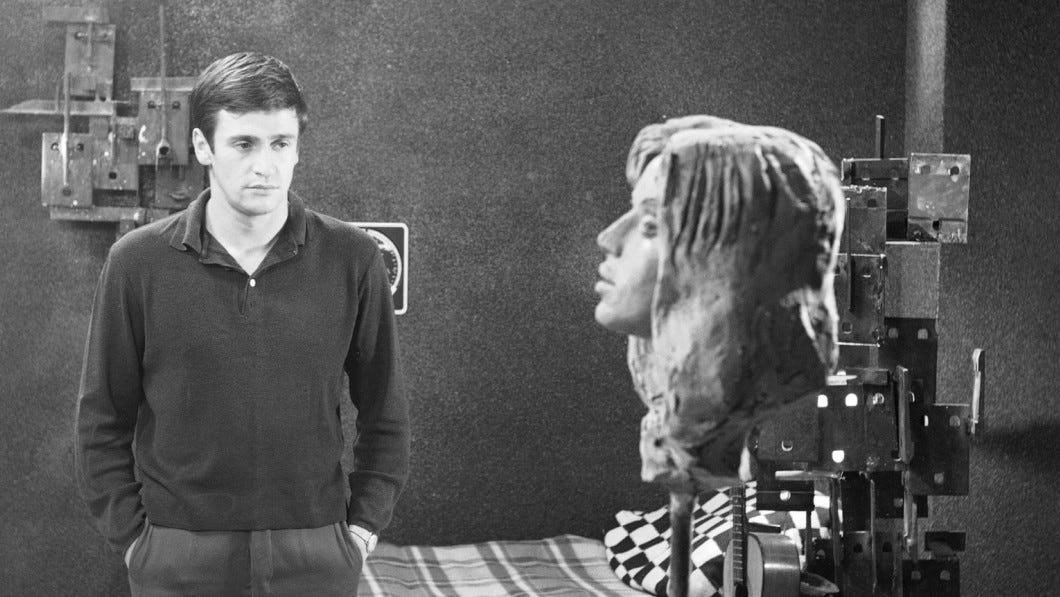

Every Week Seven Days (dir. Eduard Grečner, 1964, Czech Republic)

The previously mentioned blackout opened Every Week Seven Days (1964), the debut of Slovakian director Eduard Grečner and part of Rotterdam’s Cinema Regained strand. It follows two university students over the space of a week, making grotesque statues, dating women, dancing and walking around the beautiful city of Prague. At all corners, the threat of the nuclear bomb lingers, with joyous scenes of youth movements undercut by voice-over recollections of Hiroshima. There is joy, confusion and true horror all at one time, emphasised by Ilja Zeljenka’s droning, stunning electronic score.

The film loses its way the further it leans into shenanigans, with glides into romantic misadventures dragging when sat right next to heavier moments. It is never less than beautiful — a horned-up, bleary-eyed evocation of what it means to live in a world where it could all end at any moment. “What sense does it take to decorate a dying planet with statues?” asks our on-the-outs hero (Anton Ocelka) at one point. You understand the fatalism. But Grečner’s aching vision is a necessary screen-shot of a moment in history: if we are to die by the bomb, then remember how it felt to wait for it.

The Lady from Constantinople (dir. Judit Elek, 1969, Hungary)

This 1969 debut from Hungarian filmmaker Judit Elek is easily one of my most stressful movie experiences in some time. A war widow (Hungarian theatre star Kiss Manyi in one of her final roles) switches the flat she lives in for a place outside of the Budapest hustle. Of course, it isn’t that simple. The cramped, rusting-over building she lives in consists of a community that cannot hide their hatred even as they help and commemorate one another. As she seeks a new home, everyone she comes into communication with is simply exhausting. With the help of camera operator Elemér Ragályi, Elek slowly fills her scenes up with actors and overlapping dialogue and an abundance of noise, until you’re suddenly feeling Manyi’s intense levels of stress. It’s not often I’ve seen the everyday messiness choreographed in this way.

Manyi is wonderful as the lead, a gentle but stubborn woman dealing with the prospect of a late lifestyle makeover. Elek’s film appears to be a societal critique of then-Soviet Hungary — something I wish to read more about in the coming weeks once this restoration is seen by more people. Yet it still resonates today with its take on housing crises, post-war hangovers and how insane a crowd of people can be to your sanity.

Korean Ghost Story - ieodo (dir. Choi Sangsik, 1979, South Korea)

An episode from the popular Korean Ghost Story anthology series, this hour-plus piece of creepiness takes place on Jeju Island, a matriarchal community where women handle the fishing duty and men are expected to be lazy. Around the island, the mythical island Ieodo is talked of in hushed tones: if men make it there, they will “beat Emperor Xi” by wooing its female inhabitants or be killed. Some men, driven by their libido, leave the Jeju and go missing; around this time, things become very strange for one put-upon maybe-widow (Yeom Bok-sun).

Programmed alongside the documentary The Age of Beasts (2021), where director Jeong Jaeeun quotes at length from it, this slice of late Seventies television crept onto my list at the last moment. I’ve been hesitant to highlight films made for television on IFC, but knowing that it was rarely (if ever) screened in the West made me more than a little curious. I’m happy that I was pleasantly rewarded, not only in the charmingly janky camerawork of the era but the haunting, longing tone that washes over the film’s second half. It goes some very strange places that I loathe to spoil here, but I would recommend reading Dan Schindel’s piece at MUBI for more. Ideally, wait until Halloween, when this simple yet radical story will work best.

The African Desperate (dir. Martine Syms, 2022, USA)

While I’ll always make room here for older films at IFC, I was not going to e-attend Rotterdam and miss out on the first feature film by artist Martine Syms. For those unfamiliar with Syms, her video work utilises fictional and non-narrative forms as a way to poke at social norms and structures. Also, she is very very funny, as evidenced by her episodic project SHE MAD, her take on the sitcom format.

The African Desperate (2022) follows 24 hours in the life of Palace (fellow artist Diamond Stingily), who has just been awarded her MFA at an art school in upstate New York. She’s been stressed with work, her teachers, family, boys and living in the (fancy) sticks, so she’s ready to let off some steam. The key problem with being around so many artists is that drugs are inevitable, and Palace takes a few too many of them. In Palace’s drug labyrinth, Syms captures the sensation of fighting all responsibility with pure impulse, and the revelations that occur when we indulge our lizard brains, whether emotional, colour-swirls or the realisation you need a phone charger. Stingily is a revelation, throwing herself into Palace’s fucked-upness with great physical control — you watch her and think, how has she never been in a movie before? The film runs too long, circling the points it’s already made, but it’s easily the smartest, most audacious comedy I’ve seen in years.

Nazarbazi (dir. Maryam Tafakory, 2022, UK/Iran)

The cinematic past was mined to great results in the shorts section with Maryam Tafakory’s Nazarbazi (2022), winner of the Ammodo Tiger Short Competition and my festival favourite. Tafakory’s film examines Iranian cinema following the country’s 1979 revolution, where a mandate ruled that men and women could not touch on-screen. We are treated to a collage of films from 1982 to 2010 showing the ingenious ways these rules were skirted around (actors holding the same bag strap, sharing a lollipop or lingering their fingers nearby), alongside bursts of rage, bloody violence, billowing curtains, wild dances. It’s a celebration of artistry, emphasised by Tafakory’s layering of text over these images, expressing their own romantic pangs alongside snippets of classic poetry and Roland Barthes. But their film is also cathartic in how it mourns for years of unfulfilled desires and for sectioning off one’s true nature.

NEXT: Land of Look Behind (dir. Alan Greenberg, 1987, US)

Great piece of writing! Really enjoyed it!